BOOK DISTRIBUTION BASIC EXPLAINER

on book distribution, Ingram, sales reps, booksellers, Topanga, and publishing

Every time I look at the word “distribution” all I see is “bistro.” This morning my best friend texted me that she saw in the baby app that the name Topanga was trending. And yes, Boy Meets World, more babies born with great hair, but my mind immediately shouted PANGAEA! JUMANJI! For the record, her utero-baby has a very “normal” name and my utero-baby (once again) will be a weirdo where the barista repeats their name several times to make sure they heard it correctly.

Now you know where my head is at this week before we jump in.

On July 19 according to receipts, I tweeted (Xenaed?) the below out about book distribution.

It got a lot of retweets, and the leading gals at Hub City Press mentioned there’s nowhere to really learn about book distribution for writers. So, this is going to be an attempt at explaining why book distribution is arguably in the top three most important aspects of publishing a book for any writer.

This post is not a warning that if your press doesn’t have distribution, they will fail you, but aspects of publicity will be more difficult. A press that does not yet have distribution, but I LOVE is Malarkey Books, and also Belle Point Press (though I know both are working on it) and Belle Point actually outlines on their website all their terms anyway, which is fantastic! What I would absolutely say IS true though, is that whoever you sign with needs to be absolutely transparent in both a conversation and a contract about what their distribution and distribution timelines look like.

I want to say plainly that I am not a bookseller, publisher, or a sales rep, and these would be the people who know *the most* about book distribution, and so, you should make friends with your local bookseller, and you should ask your publisher about distribution. My knowledge of distribution is from being a literary agent, being a publicist, and trying to sort out ways to middle-woman between booksellers and distributors for my clients. I am NOT AN EXPERT, but from experience I’ve put some things together. This is a *rough* explainer, and if booksellers or publishers want to add anything in the comments (or correct anything), please do!

Okay, so the first thing you need to know is, like Amazon, Ingram rules book distribution in the US. Almost every US bookstore has an account with Ingram. Whether or not a bookseller can buy and carry your book in a store is dependent on the distribution, and most often whether they have an account with that distributor (a sales rep, or a customer care line).

Twice a year (or at least when I was an agent), big five publishers have a big sales conference (spring / fall titles), and their editorial and marketing teams are given *minutes* to pitch their (lead) titles to sales reps who then pitch bookstores. At one time, that number was quoted to me as (eight … EIGHT!) minutes per imprint. I don’t totally believe that number, but just think about the amount of time each book is getting in that case. Even if every book is getting eight minutes, EIGHT MINUTES, to get a room full of people excited + the necessary quickie information on what it’s about and why they should promote it to their booksellers and regions, can you imagine the intensity?

A fun little test would be to see if you could sell your book in eight minutes, here’s a timer. How much can you fit in there?

The big five sales reps then schmooze the booksellers (more of this years ago, I think, but still happens), and try to get their books the biggest bookstore orders and the most visibility. (Maybe this is where I should say blurbs matter in these meetings, any early publicity matters in these meetings, any foreign sales of the book matter, a writers resume matters in these meetings—and why you’re seeing such a push for author platform. You’re literally fighting for a spot on a shelf).

Small presses and independent presses often don’t have sales reps at all, unless they’re mid-size which is … complicated. There aren’t many mid-size publishers because they get bought out by the bigger publishers, take a look at Algonquin or Abrams, etc. And if they aren’t bought out, they have an endowment (Graywolf), or they’re connected to a university and independent via university press status. There’s also your Tin House, your Coffee House, your Quirk Books, which are operating like bigger publishers, but at the size of an independent press (small teams, etc). And then there’s … the endless spectrum of everyone else. Don't even get me started on poetry (which often falls in the “everyone else” category).

I don’t mean to lump all the wonderful presses together under “everyone else,” but that’s also a huge conundrum of the “indie publishing” scene at large. Some folks believe “indie” means self-published, and some folks realize “indie” is this huge expanse of publishers that are not, by any means, all created equal. That’s the thing to love about scrappy indie publishing AND the problem explaining where you and your book fit, or you and your publisher fit, particularly to people that are not writers or publishers (aka my family and maybe yours too).

So, now—if your book is published by a big five publisher, or distributed by Ingram, it will be available through all the major sales channels and big box stores because these are the publishers who have sales reps and these are the distributors that bookstores have relationships (and buying accounts) with. Ingram has a lot of hoops for a new publisher to get through before they’ll accept distribution (it is an application process), not many small presses are going to be distributed by Ingram.

Part of this is actual, tangible, reasoning like the thickness of a book. Ingram won’t distribute chapbooks because the spines *usually* aren’t visible on a shelf. The same problem goes for some poetry collections. And there are, of course, expectations about sales, about growth, about design and function, that Ingram considers before taking on a press. Ingram also has specific buying and selling rules (percentages that they offer bookstores, whether or not they’ll allow returns on books—book remaindering, price of books—yes distributors often determine how a book’s price points sits), and some small and independent presses can’t work within those margins. This is why when you look at a book contract, or what a press (and therefore author) makes on a book, there are so many tiny percentages to think about. Things a press should always care about, but might not have the bandwidth to meet in the first several years of publishing, or ever.

The other thing to know is that Ingram can warehouse and distribute books that they aren’t the distributor for, which is … confusing. And because bookstores very often order from Ingram, it’s like a horse and pony show. Ingram orders a small batch of copies from the distributor and then warehouses them. The way they decide on those orders (how many books, etc), I truly don’t know. Those orders are often small or print-on-demand (I’m talking like five copies of a book), and will not support bookstore events or a tour. If those five copies run out, the book will show “backordered” from a bookseller perspective and they will not be able to place an order with Ingram (this also is true with Barnes & Noble and Bookshop.org, if you see backorder, this could very well be a distribution dilemma that will not be easily solved).

They also have a print-on-demand service which is different than their traditional distribution service (see what I mean by monster?) and they stock books that way, but aren’t a traditional distributor with sales reps and all that for their print-on-demand clients. The press would be doing the bulk of reach outs, and would be acting as a sort of sales rep (impossible with a small team to do this job too), though bookstores CAN order those books on demand, so copies will be available for events. WOOF. I feel like I’ve run out of breath.

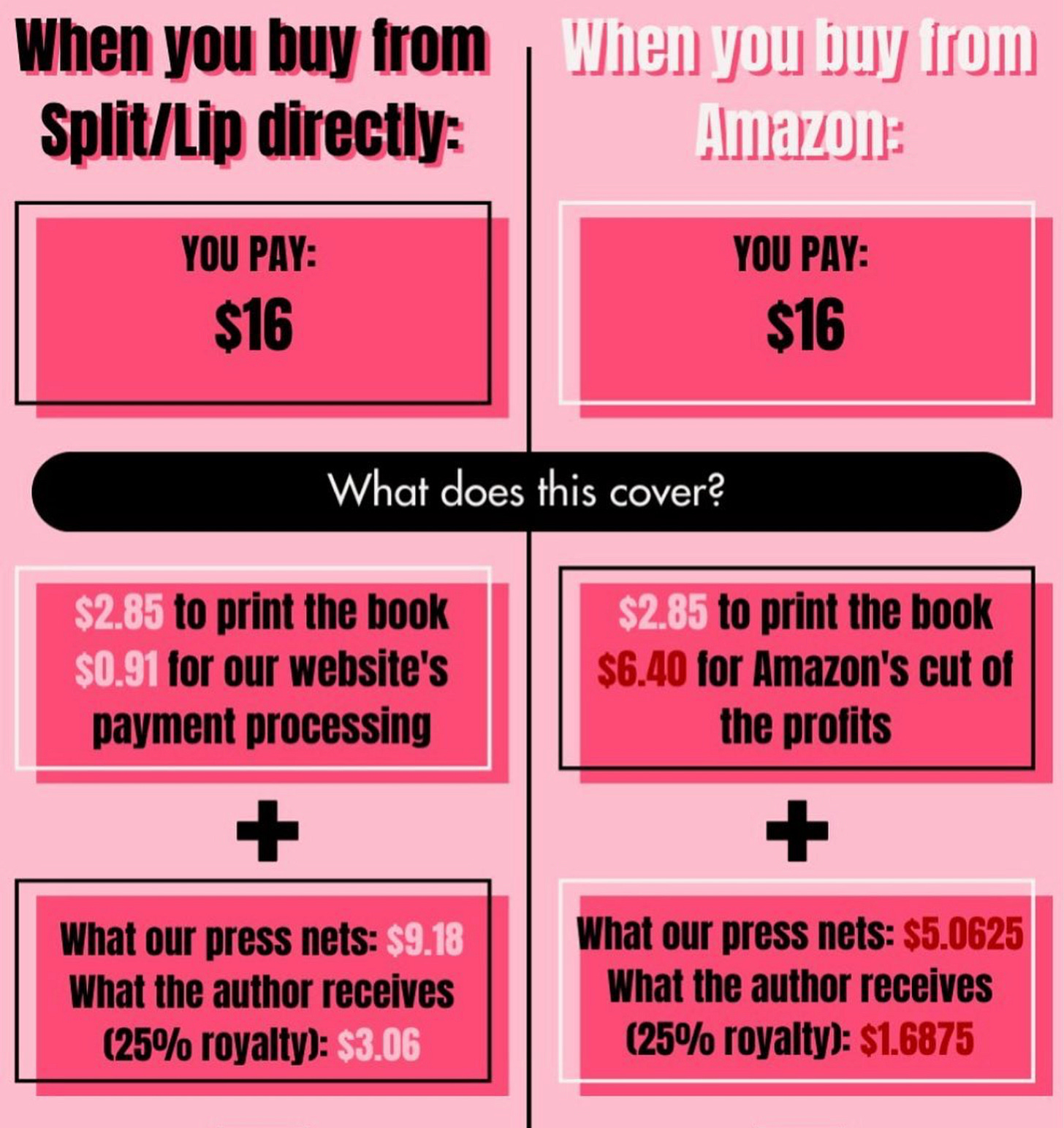

This isn’t quite the same, but I LOVED this graphic from Split Lip Press about percentages with Amazon. Amazon LOSES money on books. Books were a way for Amazon to enter the market (a niche) and now they LOSE money on books in order to get you to the site for the mindless scroll of “other things.”

Bookshop.org, for example, our beloved alternative to Amazon built by the man behind Catapult, Literary Hub, Electric Literature, Andy Hunter (can one man be a publishing conglomerate?), uses Ingram distribution. That’s how it was built. They work with other distributors now, but for a good year they only listed Ingram books. In essence, Ingram is the Amazon of book distribution—they’re the monster.

That being said, there are so many brilliant smaller distributors (or genre specific distributors—like art book distributors for museums, for example), that are working to get visibility and shelf space for authors. Chicago Distribution works with several university presses, Longleaf works with several university presses, IPG works across the board, Small Press Distribution is like the poetry capital of the world for distribution, Baker and Taylor is your main library distributor or where most libraries have a distribution account, National Book Network works with a ton of presses (I will say I’ve had trouble with them in the past—their margins are a little rough and it makes it hard for booksellers to buy from them, in some cases bookstores would lose money shipping the books, BUT … that’s a whole other story).

The Nonfiction Booksellers Association has a list of distributors that you can peak through, as does the IBPA. Wikipedia of all places has a list. That Wikipedia list also has distributors in audiobooks (which are often different distributors to the print book distributor).

There are A LOT of options.

And your distributor is often where your books are warehoused, how galleys are shipped, they determine your regional sales reps, determine whether you’ll have books for the conference you have upcoming or that book launch event, choose release dates (not to be confused with publication date, but when they release books from the warehouse for bookstores and retailers, which yes, can be pub date, but also can be different), are beholden to printing dates (though they are not often printers, but some do print-on-demand services) that may shift and change, and determine how many copies of a book from another distributor to buy and then … you guessed it, distribute.

And there ARE other ways to get your books in bookstores, but it means you hawking the book around. There are regional booksellers associations that you can contact (mine is SIBA, the Southern Independent Booksellers Alliance), and you can sell your books to bookstores on consignment, meaning they buy them directly from you and then return them to you or the publisher if they don’t sell.

There are some bookstores who will absolutely not book an event with an author if the book is not on an order or they haven’t been pitched to carry it. Powells in Portland is this way, which means the publicist is reaching out to the publisher to see if sales reps have pitched Powells yet or to see if an order has been put through the system so they can then pitch an event at Powells. Authors can submit the book themselves as well.

See what I mean by complicated?

This is all to say, distribution MATTERS. And this *very* basic distribution overview is also all I know as a publicist and former agent. It’s a quagmire. I’m not a bookseller so I don’t know what exactly the buying side looks like, and I’m not a sales rep so I don’t know what’s convincing in that department either.

So, here are some other sources that might be helpful:

📚Jane Friedman, The Value of Book Distribution is Often Misunderstood by Authors

🎧 Pub Date Podcast, Book Distribution 101

📺 Alexa Donne on Youtube, Bookstore Secrets! How Publishers Distribute Books

As always, the Pine State calendar of events lives here. Request books for review & interview & feature here, add yourself to our reviewer list here, and buy our books here! You can also contact us through our website, Pinestatepublicity.com.

ICYMI: Eugenia Leigh wrote a beautiful essay for ROMPER “Motherhood Brought My Buried Rage to the Surface”, Lit Reactor loved Kate Doyle’s story collection I MEANT IT ONCE, and Joyland is also giving away a copy of the book on Instagram, Beth Kephart did a beautiful interview in Women of Letters and published a piece for Biblioracle on Judith Kitchen’s The Circus Train, Kirkus wrote too many nice things about her forthcoming book MY LIFE IN PAPER to even share a pull quote, Richard Larson wrote a great review of John West’s Lessons and Carols, Kate Doyle published stories in Lit Hub, The Millions, and Joyland from her debut collection I MEANT IT ONCE, and Kerry Chaput wrote about letting teens read sex scenes for Mutha Magazine.

I want to make this required reading for every one of my creative writing MFA students.

such a smart and helpful post on a very complicated thing!