Down the (niche) rabbit hole

In which I discuss Willy Wonka's tunnel of terror, transformation, book diamonds of the season, and the fun house doorways of pitching your (future) book + a prompt from Sara Moore Wagner

But first, A PROMPT from the wonderful poet Sara Moore Wagner (who has TWO books and a chapbook out in 2022). Here goes: “Many poems in my forthcoming book Swan Wife are half-persona poems I wrote to explore and dismantle what the world "Housewife" means. For example, my poem "Housewife as Rumpelstiltskin'' (featured in SWWIM Everyday) juxtaposes a housewife speaker and Rumpelstilskin, figures who seem to have nothing in common on the surface. I have many of these kinds of poems in Swan Wife, from "Housewife as Anastasia Romanov" to "Housewife as an August Morning." Think about a word people use to describe you, your job, or your identity, that feels like a stereotype. Then, think of something else that feels opposite or in conflict with that idea. Rumpelstiltskin, for instance, is a menacing, destructive force, a trickster, as I mention in the poem. When you think of a housewife, he is not a character that comes to mind. Combine the two ideas you came up with. The weirder the better. How can one be the other? How are you both?”

I remain convinced that the reason most books aren’t sold (or sell well) is because of an inability to whittle them down to their richest parts. Yes, yes, the pages are most important, but the doorway to the pages is the pitch. Some people call this an elevator pitch, others a synopsis, a summary, back matter, a spiel.

But where most of these pitches include the big themes and the summary of the book, I want to talk about the curious parts. Those parts writers spend years picking at, reorganizing, rewriting, revising, until HUZZUH, like a Mary Poppin’s bag, those parts reveal themselves, and so a writer digs further and further, falls into the strange universes of their minds and hearts and thus, a book is born. [breathe!]

Fairy tales are so good at this. Take Alice for example:

The reason everything becomes “curiouser and curiouser” is because of the objects detailed in the opening scenes. The bread that grows her three sizes. The viewfinder key hole where a white rabbit wearing argyle and carrying a gold pocket watch scurries away. The schnoz of the knob. The changes in tunnel color from dark to sick neon. The way her dress parachutes out and catches air. All the ornate patterns of the antique furniture she floats by, a distinction between the time she’s in and the time of wonderland, which is perpetually behind and ahead.

There are so many scenes like this in our worlds of the fantastic. The Willy Wonka “Tunnel of Terror” in which Wonka loses his whole damn mind for a few minutes on the river. I’m still traumatized by it, honestly (millipedes & a beheaded chicken—why!). And it’s no mistake that in plot-time, that scene comes right after Wonka finishes singing “Pure Imagination.” We’re entering behind-the-scenes of Wonka’s factory. Layers on layers. First, the public stays behind the gate, then, the golden ticket patrons see the candy garden and Augustus gets sucked into the chocolate river chute, and then, (like clockwork) after danger has been revealed, (re: imagination) we enter the tunnel.

The reason we continue to have the argument about books as art, education, enlightenment, entertainment, or all of the above, is that what we’re asking folks on both ends of the book to fall down the rabbit hole. Writers into the initial germinated seed of an idea AND readers into the moment it’s cracked open on a rainy afternoon. We are essentially asking at the beginning and the end for our communities to ride through the tunnel, to transform. Writers choose to enter their own gravy brain, choose a doorway that leads to several other doorways until they come out some other fun house side, and readers choose to follow the author into that foreign space of another person’s mind. All books have this in common regardless of genre. They are all *fantastic* in their own way because of this.

Unlike Alice, however, a writer’s doorway doesn’t speak to us about drinking tea and eating bread, and the only visible trinkets in our tunnel to convince readers to continue are a synopsis, blurbs, a cover, and eventually coverage (which is largely driven by financials and what I call “being professionally annoying” aka follow-up).

And writers don’t have a whole lot of control over any of these. Blurbers can be suggested and asked, a contract can say a writer gets cover consideration but usually a publisher has final say, the synopsis (back copy) is written in combination between an agent and an editorial team (sometimes taken from an author’s initial query letter), and publicity & marketing is determined by size of your press, distribution channels, and where you fall in the publisher’s line-up, or how much they paid for the book (and whether you can afford an outside publicist). So why, you ask, am I writing to authors about their book pitch?

Well, two reasons: the first is that a good book pitch goes a long way for an author in the eyes of an agent or editor—it tells them you know your book to its most kernel state, you know how to talk about the book, you have a vision for who your reader is (based on the adjectives you’re using, the descriptions, the tropes, the language and ideas), and that the book can be packaged down to some sort of sales-y script for booksellers, bookshelf browsers, and sales reps. (I know, gross…)

But the second is that as a publicist, I don’t usually use these packaged synopses. Sure, I slap that editorial synopsis into a press kit (example press kit for Curing Season by Kristine Langley Mahler), but when I’m writing pitches to reviewers who might consider covering the book, I’m thinking about new doorways that go beyond summary, theme, and central questions.

It’s a different pitch than what I might write as an agent hoping to sell the book to an editor because my audience has changed. For example as an agent, I learned this week that when the brilliant Monika Woods pitched Amy Fusselman’s The Mean$ to her editor, she wrote, “I hope you’re reading this by a pool, a lake, or a beach.” Now, I might steal this for Amy’s publicity pitch, or I might say something like “The Means is going to be THE Hamptons book of the season.” (like the diamond of the season, only this time for beach reads) or “a splendid read for your next long weekend!” or “pack The Means for your next weekend getaway!”

The reason for this slight but meaningful change in how I’m pitching the book is that in just a sentence I’m giving reviewers a time and place for the book. I’m also telling them the audience for the book, I’m making sure the book is seasonally on their radar (hello fall / beach read anticipated lists!), and I’m connecting the book directly to “vacation” aka a time of hope, happiness, and wonder. I’m asking them to go down the rabbit hole.

This might seem like something simple, and it is, but I think sometimes writers forget that each new audience that you want to reach also needs a new pitch. What (rabbit hole) richness speak to the food & culture editors for Jehanne Dubrow’s Taste: a Book of Small Bites, is not going to necessarily crossover to her Texas audience, or her poetry audience, or her Jewish audience. Each audience has their own needs, and thus each audience wants a separate doorway for which to enter the book.

So, here’s what I think about when I’m pitching a book:

We went over this already, but who are the layers of audiences? Who, large scale to small scale, is going to love this book or could want to enter this book.

What other books & writers might this audience like that have crossover appeal with the book I’m pitching? (Yes, friends, your comps take you far, far away).

What is the essential aboutness for this audience—what MUST I get across about this book that will make them request a galley or buy it? Think on the scale of an atom. Drill down, and drill down, fall deeper and deeper.

How do I connect this book to our time & place right now? (For example, Kristine Langley Mahler’s Curing Season: Artifacts is about assimilation and trying to belong in a community that has “settled traditions” which feels very right now). This is maybe one of the most important pieces of the puzzle: timeliness. Ask yourself: Why this book? Why right now?

Funnel down those main themes into moments. People have to be able to picture themselves with the book, they have to be able to IMAGINE.

*

For S. Yarberry’s A Boy in the City, the Deep Vellum synopsis reads:

“A Boy in the City uses poems as pillars to interrupt and excavate an interiority that unfolds and interrogates grim thoughts and intimacy. Yarberry weaves a sexy, glitzy journey through their city, where the speaker can “pose” and “compose” in a “trans way, of course.” Clever in its playful allusions to Greek myths, William Blake, and other literary figures, A Boy in the City is a distinct work of joy and liberation that reckons with the language of gender and desire.”

*

Part of my pitch reads:

“I am so excited to introduce you to A Boy in the City which interrogates how our bodies both seduce and elude. Told through the lens of an intimate partnership, Yarberry explores the way we inhabit and are simultaneously distanced from our bodies–our loose seams, our disappearances and infinities, our longing among the brilliance and mundanity of the “streets and lights and strangers” of our cities.

The collection feels like an easy Sunday morning a few months after a break-up; a raw nerve, romantic and splintered. I think we need collections like this now–to read poems where a queer writer navigates the fine lines of pleasure with equal parts bliss and craving. Through this voice, we remember love, like so many of our emotions, is felt through the body, and Yarberry bravely manifests that grim yearning on the page.”

*

The shift is that I want people to enter the book knowing it’s a story of love and heartbreak, that the connection point between them and the book is that experience, those feelings. This pitch is also especially poetic because I’m pitching poetry. My language should speak to my audience—think about accessibility. I haven’t mentioned William Blake because it’ll take a specific audience for that one (scholarly? academic? classics lovers?). Greek myths are perennially very sellable, but that’s also for a different pitch.

A good pitch at its most basic, like we’re told from every high school teacher ever, includes the classic logic, emotion, and trust/ethics (timeliness?), but so often what we miss is that most human component of emotion.

You know how I know it’s a good-ish pitch? Exhibit B used it in their promotion of S.’ next reading.

Let me be clear: you should have fun doing this for your own work.

Your exercise this week is to write a sample pitch for ONE audience of your book. This isn’t Oprah, “you get a pitch, and you get a pitch!”—Start with one and build from there.

If you’re querying, think about what agents want (sellable)

If you’re pitching small and indie presses, think about how you would fit in their catalog and how you fit into their messaging and themes

If your collection is forthcoming think about one of your audiences and their needs. What’s the last book that audience really loved?

If you’re hoping to be on Fresh Air with Terry Gross, what would her producer want to read in a pitch? What do her book contributors like to read? What parts of books does Terry latch onto when she talks to writers about their books??

These questions can also help a few drafts into the book. Because you’re going to have to answer them at some stage of the writing process (aka when you get past the “art” part of the book and into the “selling” part of the book—we do live under the reign of capitalism)—use them as fuel, tell yourself as you write, “why this book, why now?” Make it your mantra. Put your answer up as a post-it above your desk. Sing it to yourself while you brush your teeth in the morning. The more you niche-down an answer to that question, the more you’re ready to sell the book (to every audience). However, there is a time in the writing process where these questions can ruin a work of art, so a writer has to know when they’re ready to start shifting to sales mode.

We’ve seen the classic comp formula: [this book] meets [this book] or [this theme] meets [this theme], but how can you go beyond that?

Anna Gazmarian’s memoir, Consider the Weight of It, is mental illness meets religion. But it’s so much more than that: evangelicalism, the south, finding your people, belonging, parsing through organized religion vs. faith, what is faith and what is the role of faith in our world today, how can we feel okay with so much unanswerable, guilt, shame, gaps in texts & trust & memory—and our job as writers is to drill down, funnel the too-large bits—get from star to stardust.

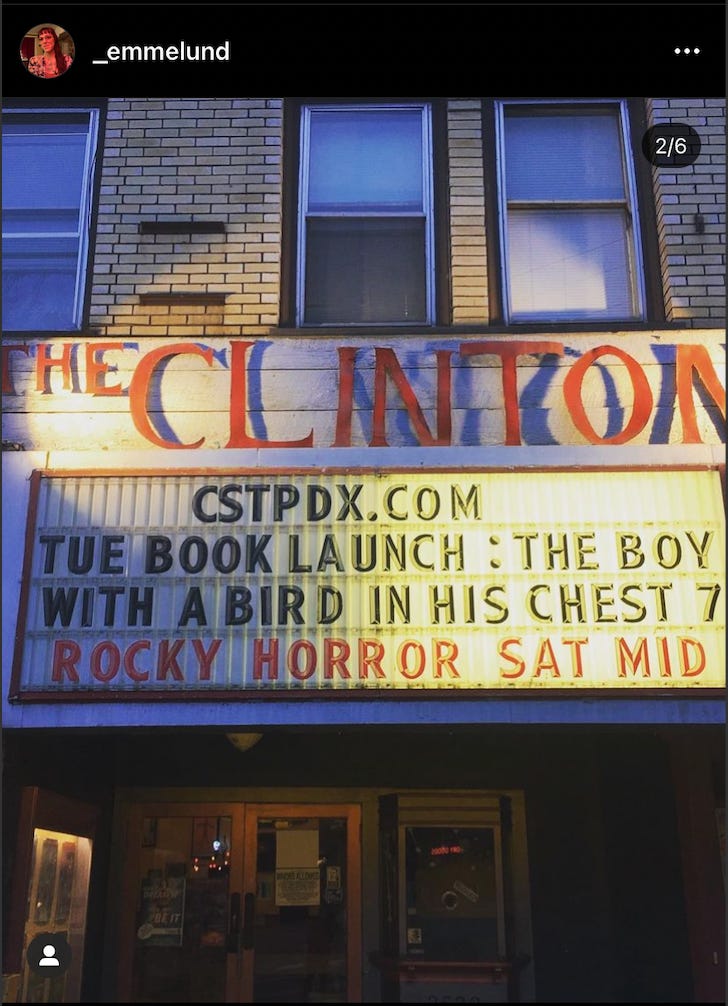

What you see in lights at the end of it all still takes the effort of placing each letter. (See this glorious sign from Emme Lund’s book launch at The Clinton Theater).

And remember, you know the parts revealed from your Mary Poppin’s bag best—of your tunnel, of your rabbit hole. You’ve fallen more times than any of us. Tell the people exactly what trinkets go where.

Buy the books I’m working on at this Pine State Bookshop.org link, from Perennial Press, Bull City Press, and Cider Review Press, and the Triangle House bookshop too!

But why does it seem so hard to answer the question, “What is your book about?” Or to come up with the pitch? Are we (am I) afraid to get it wrong? For people to be sorry they asked?

Cassie! I read this to procrastinate--and it turned out to be so helpful! (of course!)