ON VIRALITY

Yes, I'm talking about the viral Vanity-Fair-Cormac-McCarthy piece and Vincenzo Barney's response in Slate.

For a long time I believed that if I could just land a viral essay, I would get a book deal, and the journey to publishing would simply be me floating in on my bubble, pages plastered to its film. (Did you really expect me to miss a Wicked reference on this holiest of weekends. I already sobbed listening to the newest version of “Defying Gravity.” It’s true, I’m holding space).

And I hear this from writers all the time—”I’m just hoping to go viral.” But I’ve never really, except in the case of Sabrina Orah Mark’s “Fuck the Bread. The Bread is Over.” in Paris Review, actually seen a viral essay serve a writer beyond the illustrious book deal. Which is the goal, so maybe it’s not that bad. (If you haven’t read Happily, I urge you to get a copy). In fact, it seems like critics and readers alike, go into books by viral essayists looking for a flaw.

Side note: I admitted in a Tiktok comment recently that I believe (now, after being a few years out) as a literary agent, as much as I said aloud this wasn’t the case, I was reading for a reason to say no, rather than a reason to say yes. Maybe I’ll have more to say about that. This is the same deal that (I think!) faces a viral essayist when their book hits shelves. Will it live up to the OG material?

I’m not sure if it’s jealousy, or the peak of expectations reigning down from the tippy top of virality, but from “Cat Person” to “The Crane Wife,” “Bad Art Friend” (court outcome detailed here) to “The Protagonist Is Never in Control”—it’s like there’s a bonfire, and it feels great standing near it for a while, but eventually (either by the author’s doing or the turn of the masses) it burns the entire forest down. Sure, CJ Hauser got a book deal for The Crane Wife (at auction, but she had sold a novel already—so another book was likely), and “Cat Person” published the collection of stories, and then I believe, a novel.

… But CJ Hauser’s collection got mixed reviews (really loved it or really hated it) and I don’t know anyone that bought Kristen Roupenian’s story collection, or actually knew her name after she went viral (Including me, I’m going to leave that I called her “Cat Person” up there because it’s the truest evidence). Let’s not forget that the Slate piece “Cat Person and Me” by Alexis Nowicki, which also went viral for the controversy, and even Natalie Beach’s “I Was Caroline Calloway” in The Cut didn’t lead to book sales or glowing reviews. What they did all get though, is a book deal—so maybe we’re living in the halfway house of the dream. The promise is a book deal, not praise or sales or love. That part is a harder get.

There have been viral essays that I’ve never seen result in anything. “Scenes from an Open Marriage” by Jean Garnett for example. But most, tides turn.

The latest viral essay to sweep the social media wastelands got … almost no praise? Even though most of the arguments against the piece (aside from McCarthy’s death year date which was wrong when originally printed) are about writing style and taste. Here’s one kind post I saw on Blue Sky earlier today.

Yes, I’m talking about the Vanity Fair piece by Vincenzo Barney on Cormac McCarthy’s longtime muse, Augusta Britt. Called “the greatest literary scoop” by Dan Kois of Slate (in an interview I’ll talk about below), Vincenzo Barney got a mysterious comment on his Substack after reviewing The Passenger and Stella Maris, and the opportunity of a lifetime unfolded for him. (The fact that Britt’s comment arrived in his inbox on April Fools is just icing on the cake here).

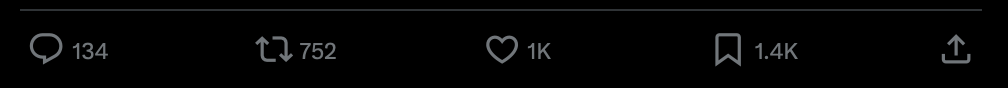

These are the current stats just on the initial Vanity Fair post on Twitter. It’s been crowding my feed, and everyone who is everyone has a (mostly salty) opinion.

I was mildly distressed to see some of my favorite writers in Barney’s mentions telling him what a horrible writer he is, among other terrible things about his Twitter profile photo, and definitely his moral stances on a situation in which he (I’m reading into this from interviews) felt very obliged to the narrative of his source, Augusta Britt. It seems to me, Barney did not fray (or argue against) that narrative in the slightest, a choice, but one that does honor Augusta Britt’s telling of her own story.

I guess I was surprised by the amount of vile things said about someone who is, if we would be defining him for a grant application or a Tin House scholarship, an emerging, un-bylined writer. He has a BFA from Bennington and writes a Substack. He is someone’s student, a son, a person, offline. I realize that he got paid by the word for this profile and it’s published in a dream magazine for many, about a writer who is so beloved (Cormac McCarthy), he’s practically untouchable, but what was Barney’s other option? Recommend Britt to someone else, when his dream was right there?

All of the above comes with tinges of jealousy, anger (of course) from McCarthy scholars who have made studying him their life’s work, and blowback from the stakes of the story’s framing, but it all made me wonder how someone else might write the piece having spent a year with Augusta Britt, trying to tell her secret-for-a-lifetime story in some sort of “right” way, when nothing about the story fits the narrative of “right” or “good.” Barney made a choice, and he stuck by it.

I can’t defend the writing style, the moral nuances (if they exist) and any framing / structural choices, because they weren’t mine to make, but I do want to talk about what Vincenzo Barney did next from a publicity standpoint.

Dan Kois of Slate, “scored the scoop” (Forrest Wickman) of interviewing Barney after the Vanity Fair piece. Kois does nothing to attempt to hide his own feelings in the introduction of the interview saying, “However, that serious criticism has been somewhat drowned out by the gleeful clamor of people quoting their favorite Vincenzo Barney lines. Because, when the greatest literary scoop he was likely to get in his lifetime landed in his lap, Vincenzo Barney did not phone it in. He spent nearly a year living in Arizona, talking to Britt basically every day, and when he filed to Vanity Fair, he did not file a careful, journalistic report. No, he really went for it, delivering the weirdest, most frequently nonsensical, most floridly overwritten story to appear in a legitimate magazine since … maybe since the heights of New Journalism in the 1970s.” And finished that introduction with, “And while the publicists may well have edited some of Barney’s responses, they sure didn’t edit out his personality. In this email Q&A, he addresses the criticism he’s received, reveals that he thinks his style is less McCarthyan than influenced by another writer, defends his characterization of Britt and McCarthy’s relationship, and playfully deflects any number of questions, while straight up ignoring one. All that is to say, he responded with the bluff bravado of someone whose dreams have come true, though I think that someday he’ll regret viewing these events in that way. His answers are presented as he wrote them.”

The questions are quite pointed. They are pressing, yet full of assumptions. I’m especially curious about the question of finances, as we live in a culture that both wants writers to stop viewing themselves as “starving artists,” but doesn’t want them to be rich with an easy avenue into Vanity Fair either. Best to be middle class, but definitely not live in suburbia. Best to be supported, but only on the level of failing to launch or returning to your childhood bedroom after graduating college, and not financially spending nine months in the desert with your favorite writer’s favorite character swatch. Best to not write personal essays, but must believe in a “writer brand” built from a writer’s own social media channels. There’s no “right” avenue, other than honesty.

I can never help thinking about Didion’s wealth when I think about the way we dissect writerly finances. In my head, I think of her as a sort of classy Dorit Kemsley—is that far-fetched, maybe? But did you see the scene this week in RHOBH with Dorit being chased by paparazzi and smoking? Because you can’t tell me that wasn’t Didion-esque).

What I’m trying to say is Kois wasn’t pulling any punches—he set out with a mission to find the cracks in Vincenzo Barney, to perhaps prove Barney as unfit for the profile. As if Twitter hadn’t already done that and more.

And, at least from my perspective, that isn’t at all what happened. Instead, Barney is silly, oddly charming, intriguing (I read the interview from start to finish without turning away—this is my Cocomelon, it seems). He’s interesting, a character himself. And while Kois mentions the flourish of personality in his answers, I found them to be exactly how I would want a client of mine in the same position to answer these questions.

Where he succeeds: Barney is airy, light. The heaviness of Twitter’s takedowns on his low-buttoned-button-up, his very-Vincenzo hair, the calls that he is guilty of the same behavior as McCarthy because of the way the piece is written—none of it has fazed him in this interview.

Now, this was a written interview in which his publicist could have intervened on his behalf, but I have this gut feeling (could be inaccurate) that Barney is actively choosing to lower his shoulders here, and if he was ever carrying a shield, it isn’t evident.

Even when Kois asks directly about the response to the piece, “I can see from your Twitter that you’re definitely aware of how people are responding. Readers are really coming at you for purple prose. Is that annoying?,” Barney says, “As for my style and the profile itself, Augusta loves it, and she has great taste. McCarthy also liked my writing. I’ve received just as many complimentary and thoughtful responses from readers. Most of them have taken place, if you can believe it, not in the cesspool of X. I do want to apologize, though, for having a personality and writing the way I like to. I’ve talked to doctors about it and there’s really not much I can do. My next piece is going to be so purple, so hyacinth, so ultraviolet—whoops, there I go again.”

It’s sarcasm, obviously, but without the edge. It’s goofy.

My favorite exchange:

Dan: What was your editorial process like? Did you wrestle over style questions at all? Or was Daniel Kile, who edited the piece, receptive to your choices?

“Wrestle? At dawn Daniel and I would square off on a mat and grapple over commas, question marks. I was most receptive to Daniel’s rear-naked choke. In fact, he’s editing this interview as we speak. The bell is about to go off for the next round. I haven’t much time.”

*

I would not handle myself with such levity. My therapist would have had to deactivate all my accounts and take my mobile devices, sending me off into the woods for the next several months. Though that might be precisely where Barney is coming from—horses and carrots and steel toed boots, Britt’s ranch, the mountain ranges burning in the afternoon.

It’s as if, and this is in one of the answers I shared above, the love from Augusta Britt for the piece was enough to sail Barney through the bullshit of social media. Either that, or I need some lessons from his family on how to raise someone who can so easily roll with, not just punches, but what feels like a social media K.O.

And one more thing I do want to note from the interview is this line from Barney, “with my daringly bad style absorbing most of the controversy and opinion columns.”

He’s right. He’s taking so much heat that Augusta Britt isn’t receiving much, if any. (I haven’t seen any). Now, it could be argued this isn’t a great thing when the profiler is getting more attention than the person profiled, but Augusta Britt is firm in a story that folks oppose, are disgusted by, is illegal, corrupts their idea of a beloved literary figure, and she could rather easily be turned on in another scenario. (Particularly in a world that so often wants to invalidate women and their experience whether it’s labeled “victim,” or “muse”).

What I want to say is that Barney is funny in this Slate interview, without a hint of bitterness. It’s a 12/10 publicity performance, and the best part is that it caused even more talk about the piece, which I wasn’t sure was possible. It’s not quite a turnaround, but it is a pivoting of the conversation—something new to look at and inspect by the crocodiles—so hungry, waiting for their meat. He’s extended his five minutes to fifteen. I will revel in the curiosity of seeing who acquires his future book.

As always, the Pine State calendar of events lives here, and you can buy our books here! You can also see what we’re working on and contact us through our website, Pinestatepublicity.com.

ICYMI: Iris Jamahl Dunkle’s Riding Like the Wind: The Life of Sanora Babb and Barrie Miskin’s Hell Gate Bridge have both been named as 50 Notable Nonfiction Books of 2024 by Washington Post, Jesse Lee Kercheval’s French Girl is one of ten best graphic novels in Washington Post, Christian J. Collier’s Greater Ghost named a best poetry collection of 2024 by Debutiful, Jessica E. Johnson was interviewed by Brianna Avenia-Tapper for Writing Stories, Ruben Quesada was interviewed by Gabrielle Grace Hogan for The Rumpus, Darren Demaree was interviewed for Matter News on his new collection So Much More, Lisa Russ Spaar wrote about Margaret Ross’s Saturday for Adroit, and so much more on our Twitter & Instagram.

Cassie. I am one of those Barney parents you mention. I'd be awfully proud of you too. Brilliant essay.

barney_doug@hotmail.com.

Best one I have read on the subject. My son sent me the link, after I found it myself.

You make a lot of excellent points here. The sheer vitriol this VF piece aroused really floored me. It's obvious Britt wanted the story told this way. Would *I* have written it this way? No, but I'm not Vincenzo Barney, and I didn't spend a year in Arizona. Also, good for him for getting paid. I love getting paid a lot for magazines pieces, when possible. You're right that the view of writers today is rather absurd: it's ok to be capitalistic and sell-out (get that bag!!) but don't make *too much* or you're ... what? A bad person?