PUBLICITY AND PLACATION

when marketing copy doesn't match reading the actual book.

Sometimes I’m frustrated by the way a book is marketed vs. the way reading the book feels. Most recently, I felt this way with Chelsea Bieker’s Madwoman. I personally don’t like a book that has that quality of hyper-fictionality—where the fictional aspects feel too glossy or beyond the book’s parameters and limits, and for Madwoman, it felt more Goop-ish than “gripping” and “living in the bone.” (New York Times + blurbs). I read it quick and there were sentences to devour, and I’ll read the next book by Bieker, but I felt like the marketing and the actual book didn’t match up.

I’m intrigued about this as a publicist, the space between marketing and the truth of a book. Mostly, the ways in which we try to make our marketing descriptions match a book or, when we purposefully try to omit certain aspects of the book especially if they don’t fit a current narrative. For instance, if I knew the “satire” in Madwoman was that the main character is a “momfluencer” obsessed with “wellness” I would have never picked it up. The marketing team might have known it would be hard to pitch that alongside a domestic violence narrative (though are we sure??? because look at Colleen Hoover), and so they held back on that aspect of the book in the description, even though Clove (the narrator) is 70% supplement.

On the other side of things, I’m the first to admit that I can’t really take on any books that feel too heavy at the moment. So, when I think about working on intense books at Pine State, I think about the ways in which I can approach readers that won’t immediately say “discomfort!” or “this book will make you uncomfortable.” There’s a lot of good writing in other newsletters right now about the lack of criticism in criticism and the move to having authors write reviews rather than critics, as professionals. Ross Barkan’s recent Trust the Critic?, Elizabeth Kay Cook and Melanie Jennings on The Big Five Publishers Killing Literary Fiction, Brandon Taylor on Bringing back FICTION, in general essays by Naomi Kanakia and Angelica Jade Bastién. All of this has also found its way into marketing and publicity—it’s a kind of placation. I fear it, I loathe it, and I have also felt myself trying to employ it in pitches (particularly when a book isn’t easily palatable, but also doesn’t fit an on-going popular narrative of the moment).

I say I can’t really do heavy, and then there’s me last week picking up Fi by Alexandra Fuller from the library—who do I think I am? Fuller has a disordered writing style. Her train of thought is not sentences as stepping stones leading to a river. It is jarring, even jerky—like you’re in a car on a rough terrain. It would be incredibly hard for a marketing team to match the style of Fuller’s writing in a book description. At times, I feel jumbled reading her nonfiction—it’s purposeful. While I would love the challenge of describing her book in a pitch, it would be a feat. I can’t find an excerpt or I would share it.

Here’s the book description from Grove:

“Fair to say, I was in a ribald state the summer before my fiftieth birthday.” And so begins Alexandra Fuller’s open, vivid new memoir, Fi. It’s midsummer in Wyoming and Alexandra is barely hanging on. Grieving her father and pining for her home country of Zimbabwe, reeling from a midlife breakup, freshly sober and piecing her way uncertainly through a volatile new relationship with a younger woman, Alexandra vows to get herself back on even keel.

And then – suddenly and incomprehensibly – her son Fi, at 21 years old, dies in his sleep.

No stranger to loss – young siblings, a parent, a home country – Alexandra is nonetheless leveled. At the same time, she is painfully aware that she cannot succumb and abandon her two surviving daughters as her mother before her had done. From a sheep wagon deep in the mountains of Wyoming to a grief sanctuary in New Mexico to a silent meditation retreat in Alberta, Canada, Alexandra journeys up and down the spine of the Rocky Mountains in an attempt to find how to grieve herself whole. There is no answer, and there are countless answers – in poetry, in rituals and routines, in nature and in the indigenous wisdom she absorbed as a child in Zimbabwe. By turns disarming, devastating and unexpectedly, blessedly funny, Alexandra recounts the wild medicine of painstakingly grieving a child in a culture that has no instructions for it.

In the book description, it’s definitely being marketed as a grief book. I would normally say grief is a hard sell, but we’re in a time capsule of grief. And it may be that grief is a hard sell to readers, and not a hard sell to critics and magazines. (In general, there’s always a boundary line for books about trauma (how much folks can take)—but trauma does do better with critics). I wonder if Fi’s book description is trying to follow our past few years in grief memoirs like of Amy Lin’s Here After, Kathryn Schulz’ Lost & Found, Us, After by Rachel Zimmerman, and others.

However, In the first 30 pages, Fi is a breakup, campout, rusty truck, memories of childhood book. It’s interesting to open a memoir thinking you’re going to immediately get one thing, and instead your thrust into the world in another way. I love that art does this. I’m not saying start “in media res” blah blah blah, I’m more interested in the routes writers take to get to what a publisher thinks is the “heart” of the narrative. What then, becomes the gut? the brain? the limbs? the toes? And how much space writers are given to get there. All that advice on the internet says that agents make their decisions about books in the first ten pages (can confirm) and I see writers complain on social media that their story doesn’t even start there—so what’s the happy medium? And are prolific writers given more elasticity on how long their central story takes to a develop, or more leeway in what other cilia they bring into that cell (look at me, being all biological!)

That leads me here.

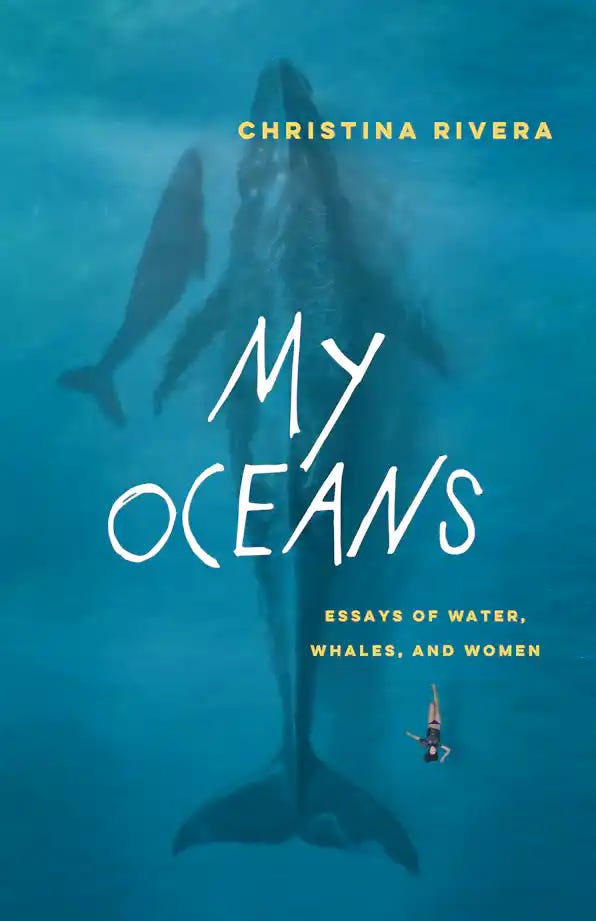

A few weekends ago, I read this incredible essay in The Cut by Christina Rivera, “My Connection to Corky the Orca and Her Glass-Shattering Cry,” from her forthcoming book My Oceans: Essays of Water, Whales, and Women. And I thought to myself, “this is one of the best essays/excerpts I’ve read in a while, and I don’t think I could handle a whole book of it.”

But the question that plagues me is that Rivera got this big publicity hit in a New York Mag publication, an essay full of emotional tenacity and very clear, time-in research, and yet—will it lead to a sale? (My sale?). This is the book, I don’t need to read the description because I read the excerpt. I don’t even care how they’re marketing it, because the excerpt is so absorbing.

BUT let’s take a look for purposes of writing a newsletter. Here are my little thoughts on the book description (my thoughts in italics / parenthesis):

An urgent exploration of caring and mothering on a planet in crisis (this is purely trying to fit a narrative we’re overflowing with at the moment (I am not complaining)—mothering + climate / braiding caring for the planet with caring for the people). I’m not sure I’ve ever seen a climate crisis book without the word “urgent” as a descriptor, so it’s time to switch things up. I am wondering too about “exploration” here, which is an interesting choice in a book of sea narratives and the connotations of that word. I also wonder with this tagline—who are we leaving out or who will read that one line and not think twice about buying).

In a swell of sea-linked essays (sea-linked is cute! + swell, I love the call of the sea in the language here), (they should introduce her since this is a debut and she’s got a fierce background for writing the book. I know this is not the traditional way of “book description” but no one reads an author’s bio). Christina Rivera explores the kinship between marine animals, humans, and Earth’s blue womb (Earth’s blue womb is stunning! 10/10). Rivera’s investigative questions begin with the toxic burden of her body (but what does this mean? “toxic burden of her body”) and spiral out—to a grieving orca, a hunted manta ray, a pregnant sea turtle, a spawning salmon, an “endling” porpoise, and the “mother culture” of sperm whales—as she redefines what it means to mother and defend a collective future. (love ending on “defending a collective future” right after sperm whales, and I also love the list of what’s ACTUALLY in the book).

Braiding memoir with embodied climate science (I think we all know it’s “braiding memoir with …), Rivera challenges that it’s not anthropomorphism to feel deep connection to nonhuman species and proposes that gathering in collective grief (would have found another way to say this because grief makes people nervous—grief is a HARD sell, and “collective” is so strongly used in the first paragraph) is essential amid the sixth mass extinction. For ecofeminists, fans of Rachel Carson (intellectual) and Terry Tempest Williams (memoir)—and for anyone who feels themself disintegrate in the presence of the sea (We need a new comp beyond Terry Tempest Williams for the eco-memoir, and I love the phrase “disintegrate in the presence of the sea”—who among us have not felt its largess? This phrasing brings people in, while the rest of the description niches, it’s a nice component)—My Oceans offers a timely and wondrous descent into the deep waters of interconnection in which we swim. (Let’s retire the word timely, everything is “timely” in its time).

It looks to me like the book description matches what I read in the essay, BUT the emotion of the essay went to the wayside for the intellectual in the book description. The closest we get to emotion in this book description is all metaphorical and/or language-driven. A bummer. The book description is saying THIS IS A CLIMATE BOOK BY A WOMAN WHO IS A CAREGIVER, when I wish it had a little bit more of the actual urgency of the essay.

I’m being picky, but saying “urgent” and feeling the urgency are two different things. This is what agents mean when they say they want the query to share the stylistic vibes (& language & voice) of the book itself. That’s what I want our pitches to do too when they land in inboxes. If you want to call your book urgent, agents (& all the turtles all the way down) want to read a query with that feeling of urgency, rather than the description of urgent.

Full disclosure: I wouldn’t have bought this book if I had only read the book description. I needed that excerpt, Rivera’s voice and the way she argues her point, to preorder the book.

It’s interesting because I did buy The Quickening by Elizabeth Rush, which feels in conversation with My Oceans. I think it’s because that book was marketed similarly but as “hopeful,” which I need when reading about the climate crisis. Also, the book description from Milkweed tells me exactly why Rush is the person writing this book—she’s on a vessel seeking, “the elusive voice of the ice.” The framing here is appreciated too, “a new kind of Antarctica story”—which speaks to the fact that this is a woman’s voice in a narrative space traditionally “claimed” by men, and gives historical-context to Rush’s narrative. This is what I was trying to say about the word “exploration” up there in the description of My Oceans—it’s calling to that history without giving context or explaining why.

And for full, full disclosure: below is my “general” pitch for a poetry collection I’ve been working on, Jehanne Dubrow’s Civilians (if you want to check out the book description or buy a copy). I don’t like pulling apart someone’s hard (and good) work without being vulnerable with my own. I hope this pitch speaks to what I mean when I say the way that a book is described should be a voice in harmony with the book, not “about” it. I also realize a book description is doing something different in marketing than a pitch is meant to do, so they are serving two different purposes. It’s an apples and oranges predicament.

And please know, much of the language in this pitch is directly from Dubrow and the poems. She is a brilliant, particular writer with a voice that always moves me. There’s a poem in Civilians about Odysseus in older age toiling in his orchards that I think about (still!) daily.

General pitch: “Following Stateside, which was featured on NPR’s Fresh Air, added to the US Naval Academy studies, and made into a one-act opera, and Dots & Dashes, featured on This American Life–in the final book of poet Jehanne Dubrow’s acclaimed military spouse trilogy, Civilians (LSU Press, February 2025), her husband returns to land, all his history precarious, her gaze splitting him into shards. Here, the loom of our wars is untangled through the story of marriage.

“I bring our war into my bed each night and barely

move in its trembling light.”

For two decades, she pinned ribbons to the hull of his chest. Yet when her husband leaves his uniform for the last time and returns to her in Texas, the ship inside him–full of passageways and shifting lights–remains afar.

In the long parade of after, there is discomfort, the word divorce, repeated moments of “Thank you for your service.” While he feels for the blade his body was, she feels in the dark for the iron edge. A candid look at a loved one transitioning to a new reality as a noncombatant, Civilians attempts to chisel down the open spaces large enough to hold all kinds of absences. Whether he is beneath the low rumble of a ship engine, or folded velvet in their shared sheets–there is a cleaving.

In conversation with the classics, including Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Homer’s Odyssey, Euripides’s The Trojan Women, and Sophocles’s Philoctetes, Dubrow carries her love like a blood diamond too tight on her finger–too pristine for this new kingdom with her husband, in conflict with himself.”

As always, the Pine State calendar of events lives here, and you can buy our books here! You can also see what we’re working on and contact us through our website, Pinestatepublicity.com.

ICYMI: Sarah LaBrie’s No One Gets to Fall Apart is named New York Times 100 Notable Books of 2024, LaBrie was also interviewed by Brad Listi for Otherppl, Booklist says A Death in Diamonds by S.J. Bennett reads, “With gripping intrigue from the very first page, this could easily be read as a standalone,” Christian J. Collier, author of Greater Ghost, is named as part of Poets & Writers annual debut poets list, Sarah Lyn Rogers’ Cosmic Tantrum is on the Debutiful Most Anticipated List for 2025, NY Sun gives Sanora Babb her due with review of Iris Jamahl Dunkle’s Riding Like the Wind: The Life of Sanora Babb, Jessica Jacobs publishes an essay in Niv Magazine, Boise State Public Radio listeners recommend Riding Like the Wind: The Life of Sanora Babb, Inquest names The Warehouse a top book in their Year in Books, and so much more on our Twitter & Instagram.

I thought this about the memoir I’m Mostly Here to Enjoy Myself, which was marketed as being a very sexual book, when really the sex scenes are not the main thrust (sorry, had to) of the book at all. Then I heard Glynnis speak at The Red Wheelbarrow in Paris, where she addressed this. She said she thought of the book as more a love letter to female friendships — and her bike! The sex angle was all marketing. And apparently reviewers/readers wanted the sex they thought they’d be getting. (Her advice that day: women readers want sex scenes.) Thank you, as always, for this deep dive into marketing and publicity!

If someone could explain which writers get pitched as literary fiction, that’d be much appreciated. Because it doesn’t seem to be based on the writing sometimes. Case in point: Kiley Reid. Second case in point: Chelsea Bieker. I liked Madwoman but it read a bit cutesy, with some convenient plot twists. Calling it emotional suspense was a stretch. I read a review of her work recently that described her as a literary fiction titan, and I think I barfed up my coffee a bit. Upmarket’s being generous.