READING AS A PUBLICIST

publicity vs. leisure reading, how different do they look?

Since I was twelve, cataloging like an archivist, I’ve kept notebooks of quotes from the books I read. If it takes me weeks to write them all down, I’ll do it. My day books, Substack taught me to call them this year.

My toddler has added Where The Wild Things Are to our nightly reading rotation (nothing beats Dump Truck Disco though), and every time I read this page, I think of those notebooks. “Through a day … in and out of weeks, and almost over a year.”

During graduate school I filled my preferred notebooks with maps, quotes, thoughts, lists, drawings, whatever routes my brain was taking that week. The accumulation helps me write my own work. I haven’t kept the practice up over the last few years of birth and grief, but I’ve been returning to it recently. I also rarely read these notebooks back unless I’m looking for something specific (Leuchtturm1917 notebooks have a table of contents and I am religious about filling those in precisely), but there’s something to the act of writing each sentence deliberately down into my notebook-of-the-self that keeps the ideas or phrases locked away within me.

And while I read in a similar way when I’m considering taking a book on as a publicist (I’m still *** my favorite sentences and writing my marginalia), there’s a difference to the two reading habits.

And so today friends, here’s to reading like a publicist.

While I’ve struggled for the past few years with reading as a pleasure or leisure activity (sigh, publishing jobs and an MFA), I still read very differently when I’m reading a book for work or reading a book for funsies. At the most basic level, I’m reading for me when I read for pleasure—my own tastes, my own interests, my own obsessions. When I read for work, I’m reading to be able to talk about the book. While I used to put everything in Goodreads, I don’t even record my reading there anymore, and so sometimes I’ll read books and never mention them aloud to anyone but my library requests list. For work, my job is to figure out how to tell the most people about a book. And that starts with my first read and how that read then shapes the way we strategize.

said sometimes she feels like, “in pitching the subject of your book I will douse the spark you’ve set with craft.” I’ve felt this too. I’ve sat on writing pitches longer than I should have because I’m not sure how to get across the essence of the writing (particularly over the medium of email). I also see this idea crop up by concerned querying writers that their query letter won’t do their pages justice, that the spark of the book is “in the read.” Here are some thoughts on that:It’s true for every book on some level that a query won’t do it justice.

Being able to tell people what you’re doing in your art is a skill separate from the art itself. One, I believe, also takes practice.

Recently on a phone call with a writer we talked about how she wanted to have an intimate connection with her audience that didn’t fit well within the “brand” or “platform” or even “publicity model” that we’re working in today. We talked at length about writers who has been able to foster that intimacy. Who came to mind the strongest is Anne Carson.

When I “discovered” Anne Carson, I thought I was the only person on earth who loved her. I immediately evangelized her work to friends. And then I went to graduate school with my pocket Anne Carson, imagining myself so learned, so artistic, so unexpected, only to realize that everyone loves Anne Carson. Not only that, but everyone has a very similar experience of reading Anne Carson for the first time as I did. She’s created an intimacy with readers as if she’s ours alone.

It’s true that what Carson has created with her work could be generational, or an anomaly, or the gift of anonymity (and therefore intrigue), but I think there’s something to Anne Carson’s relationship with readers (perhaps that she refuses to imagine them or define them? I can’t say) that I’ll be studying. Her work goes against our current publicity cycle, and against the distilling of the texture of the work down to description, summary, or market. It is what it is, she is who she is. (Worth noting is Carson also that studied a subject (Classics) rather than studying writing).

One of the things I always encouraged writers to do when I was agenting is try to evoke the tone of their novel or memoir in their query or book description. Yes, queries are business letters and should do a few pre-fab or formatted things (as requested by agents), but that doesn’t mean they’re without voice. Same goes for pitches.

In a recent pitch for a book coming out in February, I wrote “This collection moved over me like hives.” It did. I shivered reading it. I felt measly (in the late 16th century measles sense). When I’m writing a pitch for a book, I’m not only thinking about describing the book, but the experience I had with the book. The feeling, the sense, the somatic, the physical symptoms of reading.

Part of writing pitches is simply paying attention. I’m paying attention to my body while I read. I’m paying attention to what I’m paying attention to throughout the book (what hooks me, what moments take me out of the pages, what moments cause me to read faster, what scenes reveal my absolute lack of poker face).

I just read a scene this morning where a character I ached for in one chapter turned out to be loathsome in the next. I was so taken aback by my own foolishness, my own love of his thoughts and daydreams, my own associations towards his goodness, only to find that he’s rotten six pages later. Plus, reading in the car, I couldn’t escape my false gut reaction to this character. It was a claustrophobic experience. I was unprepared. I could use that in a pitch. The surprise, the turn, the tightness.

When I asked my talented, clever, dazzling colleagues

and Alisha Gorder about how they read as a publicist vs. reading for pleasure, Zoe said:This is where you will note that I laugh all day in g-chat with Zoe and Alisha.

I think if you’re a writer who works in publishing (there are so many of us), then what Zoe’s saying about expanding the bibliomancy of your own work, no matter what you’re reading, feels true and maybe poetic here. But I love that she says she’s trying to “open a dialogue with my own work,” because in both reading for pleasure and reading to tell someone else—it’s a dialogue. You know yourself best, obviously, but I wonder sometimes if the way I read a book makes me much more pointed at what I’m looking for (it depends so much on what I’m working on at the minute) than reading with the expansive lens of, this whole book is a potential for dialogue, this whole book is an opening.

And I’m leaving the Hinge part in on purpose BECAUSE a publicist’s job is to absolutely treat a book like a (beloved) nickname.

Nicknames are terms of endearment, our job is to endear a critic, reader, bookseller, bookclubber, talk show host to what an author is doing, to find it important, powerful, or interesting enough that they want to talk about it. We aren’t drilling books down to some five paragraph summary, some stuffy, buzzy, pop mantra, we are bringing who we’re pitching into the group chat, into the inside joke, sharing our nicknames.

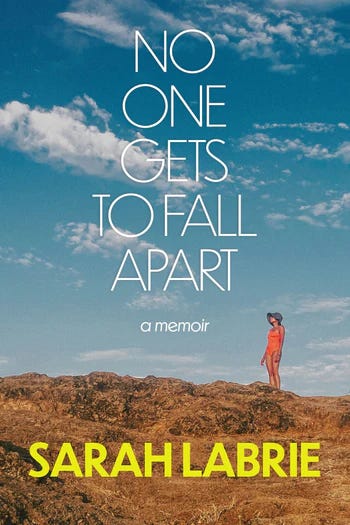

Alisha said, “I’m not sure how much I’m thinking about publicity when I read a book for pleasure, but when I read a book for work it’s a totally different reading experience. I almost wish I could have the experience of reading Sarah’s book not as her publicist. It’s a book I would love, and I do, but it’s different reading it through the lens of publicity—what stands out to me is different than what would otherwise.”

Alisha’s exactly right here, and I totally agree. When I’m reading for pleasure, I’m trying to turn off publicist brain. Same with when I read for pleasure during writing school, I was trying to turn off craft brain, in so much as you can. (Also FYI: she’s talking here about Sarah LaBrie’s brilliant memoir, No One Gets to Fall Apart). Mostly my brain is blaring a siren saying, “you should be reading for work right now! you have six books in your queue! stop reading for fun!”

Sometimes those differences in reading-for-what are subtle. I’m always reading for sentences I want to keep saying aloud or that strike me a certain way. Oddly enough, in books where I dog ear the pages with sentences I love, sometimes I’ll read the pages I’ve cornered back at the end to write the sentence down and I won’t be able to find the same feeling. I won’t know what sentence hit the me of that day. (Is this a case for re-reading books?)

But when I read for work:

I’m reading for what’s trending, which is why there’s so much value in having a diverse team on a book. We can only know the trends so far as they reach us and our core groups. I also use this trend argument when I can only delete the Tiktok app from my phone for a week and then I need either a recipe or to “know” what’s happening “for work.”

I’m reading for references (books mentioned, places mentioned, famous people mentioned, audiences mentioned). I know the genre before I start reading, but I’m reading for moods underneath that genre. Last week, a writer and I came up with a new-to-us term called “Island Gothic” or “Island Noir” for her sophomore novel. That’s mood.

I am, it’s true, reading for a basic plot summary that includes moments that I think are substantial enough for one of the book’s pitches, especially if they’re not included in the “main plot.”

I’m thinking about the type of readers that would not only love the “plot” or “story” but love the vibe. I don’t mean a mood board vibe, though more power to you, but again, once more with feeling!

This is probably where comps come in, but an example, I’m reading a book right now for work that feels like a classic (Rebecca, Emma, Persuasion, Wuthering Heights), but it’ll be published in 2025 with today’s audiences. So, where do those readers … read? Where do those readers find their books? That’s my job.

In the comp section, I’m reading for style. That book I just mentioned reads very rural to me, a little pastoral, but has this intriguing mental health component that reminds me of a Jayne Anne Phillips book, and maybe a little Shirley Jackson too. There’s a sinister moss to this book (which I LOVE as a reader), that I have to get across in a pitch without calling it a “thriller" or even a “suspense-driven debut.” BISAC (& genre) codes are not able to match that mix of mood and craft.

Reading for publicity, I’m reading less for answers or to find out what happens (like I would when reading for pleasure, HAVE Y’ALL READ THE MINISTRY OF TIME, SPEAKING OF FINDING OUT WHAT HAPPENS) and more: what questions is the book asking of a reader, of society, of truth or grief or love or some big theme, of its characters, of what can be done uniquely. Questions of craft, believability, structure the human condition? I am AP Englishing the books we work on. That is to say, I’m reading deeply, more slowly.

I am reading for where a book goes against an idea. Next summer, Zoe and I are working on a middle grades graphic novel (save middle grades!) with a pop star ghost—so, a sweet, not scary ghost. This is so simple, but it goes against the traditional narrative of scary ghosts (hi Casper!). I like to figure out what narratives the book or the author are subverting, and how intentional is the subversion?

Zoe is the agent on a book that I think will be HUGE next year, Lauren Haddad’s Fireweed, because it has the potential to be unsatisfying. Yes, you read that right. The book is doing what it’s supposed to against a reader’s expectations of what books are supposed to do. I’m actually so excited already that the reviews are kind of mixed because in my mind, they should be!

I’m reading for quirks. This might actually be my favorite thing to read for in any book. And I read for it when I’m reading for pleasure too. But it’s the part of the book that your entire workshop told you to delete and you couldn’t let it go so it made it to final print. For me, those are moments of the heart, they’re where the book is most itself. I love them, I search them out like Gretel crumbs.

And of course, I’m reading for audience. As an agent, I often thought if I didn’t immediately have a list of editors (or at least houses) where I would try to sell the book, then the book wasn’t right for my list. I think about this as a publicist too. If I don’t immediately know at least a few pitch angles, a few editors, a few media outlets, a few magazines, that might like the book, then I shouldn’t be working on it.

I’m reading for ideas for the writer, and brainstorming: talking points, companion essays, craft pieces, interview questions. This sounds more like I’m reading for the book’s world-at-large and that’s true. What’s in the stew of this book? What does the world of this book look like and who lives there (audience!)? What world is it against? That’s the sort of brainstorm that leads to really interesting work with a writer, the kind of work I love.

Remember when we did these? I miss it.

If you want to learn to read your own work this way (or you’re starting to think about non-obvious publicity for your book), I would encourage you to read a book you already love through the marketing lens. How would you angle it? Who would you pitch? How would you summarize it? What parts stick out to you? What and who does it reference? What’s the mood? What questions is it asking? I bet you’re better at this than you might think.

As always, the Pine State calendar of events lives here, and you can buy our books here! You can also see what we’re working on and contact us through our website, Pinestatepublicity.com.

ICYMI: Poetry Foundation reviewed Didi Jackson’s My Infinity and Hyperallergic featured the book, Fare Forward reviewed Christian Collier’s debut Greater Ghost, read two pieces from Jesse Lee Kercheval in Short Reads and Orion, Christian Collier was interviewed in Southern Review of Books, SF Chronicle Datebook called Sarah LaBrie’s No One Gets to Fall Apart an anticipated fall read and so did Camille Styles, Hyperallergic reviewed The Warehouse, Jessica E. Johnson was interviewed by Four Way Review about Mettlework, Esinam Bediako’s Blood on the Brain was excerpted in Literary Hub, Tiffany Troy interviewed Tatiana Johnson-Boria for Tupelo Quarterly, Chelsey Pippin Mizzi was featured on Tarot Lady’s substack, Christian Collier was on Drunk as a Poet on Payday and so much more on our Twitter & Instagram.

I love this marketing prompt!

I, too, am a fan of the Leuchtturm1917 notebooks! But I love that you commit to the index page. NEXT LEVEL!