SPEAKING OF

in which all our favorite books exist in one degree of Kevin Bacon. (P.S. This is written by Zoe-Aline Howard, publicist at Pine State, and brilliant, brilliant writer).

My home office is my bedroom plus the artifacts of my work—a yellow sticky-note mapping a conversation with Cassie where we moved from Heathers to describing a book as the poetry equivalent of glamping (spoiler alert: Cassie cleverly arrived at L.J. Sysko’s The Daughter of Man as “bubblegum history”); a Spode Christmas tree mug filled with markers for Pine State color-coding; Amina Cain’s A Horse at Night; and this morning, the writer, sculptor, and fortunately-my-agenting-client Andrea Harper’s embracing expression (check her out here). My screen offers a crack into her own office—if I could, I would steal the reaching body of a sculpture of her own, the stack of books propping up a marble, I think, shelf behind her—while we talk through revisions of her short story collection and, also, Patti Smith.

The joy of my week is in that slip. I say, I know that I keep comparing you to the Smiths, and we laugh. Patti and Ali, that is, for the way that these short stories reach into the want of Patti Smith’s Devotion, the stark pastoral of Woolgathering, and the contained voice through which Ali Smith can push the mundane toward the fantastic. Andrea and I talk at length about Patti Smith’s virtual launch of A Book of Days with The Guardian, where the author was so at home (in her home, yes, but also in front of an audience) that she raised her birthday-celebrating abyssinian, Cairo, to the camera and rummaged through her own stacks of books to find and read to us from her copy of a Gerard de Nerval collection.

This is the first time Andrea and I have talked where we can see one another, and the conversation moves naturally as we work through Patti Smith’s backlist—how Just Kids felt unjust to the Patti who cradles us in M Train, where I found my signed copy of the memoir (the Book Warehouse in the Myrtle Beach Tanger Outlets) & the $8.50 that I had to borrow from my dad to buy it because at seventeen I could only afford half a book. I share my curiosity at Patti falling into autofiction in Year of the Monkey because she wanted to lie again, after two memoirs & so much fact-checking. Andrea loves The Coral Sea, the better (we think) ode to Robert Mapplethorpe. And then there’s Woolgathering, and we just say wow.

Cassie and I have similar conversations about books, and tweets, and TikToks, all tipping into our campaigns. We see these books in everything else. Like, I sent Cassie this tweet about magpies lying on their backs, holding hands (talons? feet?), and said trying to figure out how to use this to pitch Emily—and I was, seeing so much of Emily Stoddard’s debut poetry collection, Divination with a Human Heart Attached, in these birds that Emily dreamed about & saw everywhere, offering her a hand to hold as she wrote through difficult material.

“Magpie comes to me and says, I’ll get you out.

Say the church is a broken body. I say

the church is a broken body and Magpie

laughs and says, It’s working.”

Patti Smith does something similar, finds and folds what she’s reading into everything she moves through and writes about. And in her first book of nonfiction, so does Amina Cain. A Horse at Night is a whole gift, and the book I’ve been recommending to everyone since I found it at Beacon Hill Books & Cafe (a Boston gem, which had only been open two weeks when I stumbled in, carrying my luggage for a weekend trip). (It’s worth mentioning here that I knew of Amina Cain mainly through conversations with Anne K. Yoder about event planning for The Enhancers).

A Horse at Night is doing the work—in her “essayistic inquiries,” Cain writes toward each of what I would call the tenets of Pine State Publicity: writing that thrives at the sentence level, writing that rewards atmosphere and image, rewards place, rewards joy even while drifting from it. And perhaps especially the one tenet that Cassie and I have yet to breach, rest. It’s the way that Cain talks about each of these that is so striking: like dialogue, each essay answers the previous and brings up a new book, moving “associatively through a personal canon of authors” to land at the literary space of her own life. It’s just a great book, but also, as I read, I found my own conversations with authors on both the agenting and publicity side appearing in Cain’s meditations, charms each chained somehow to the other.

And so, Amina Cain became my literary degrees-of Kevin Bacon (if you don’t know what I’m talking about, play with this: the Oracle of Bacon), an echo behind my own “speaking of.” I love every book I work on, really very deeply, but none of them, on the surface at least, have much immediately in common. And still, just in talking about finding A Horse at Night, I can talk to you about them here, all at once. Now, they do.

In conversation below: Everything else Amina Cain writes about in A Horse at Night, as it pairs with everything else I’ve talked about with authors—

When I asked Andrea Harper about the line between her sculpture & her writing, she defined it as “nearly non-existent,” even pointing to an interview with the artist Eric Fischl, where he was asked whether his paintings are literature. He said no, but she’d say YES. Referencing Orhan Pamuk’s The Naive and Sentimental Novelist in A Horse at Night, Cain writes, “But what if you are a short story writer or a novelist interested in something other than story? What if when you look at a piece of art there is something in it you want to try in writing, because to you it seems as if a story should be able to hold something like that, hold possibilities, not exclude them.”

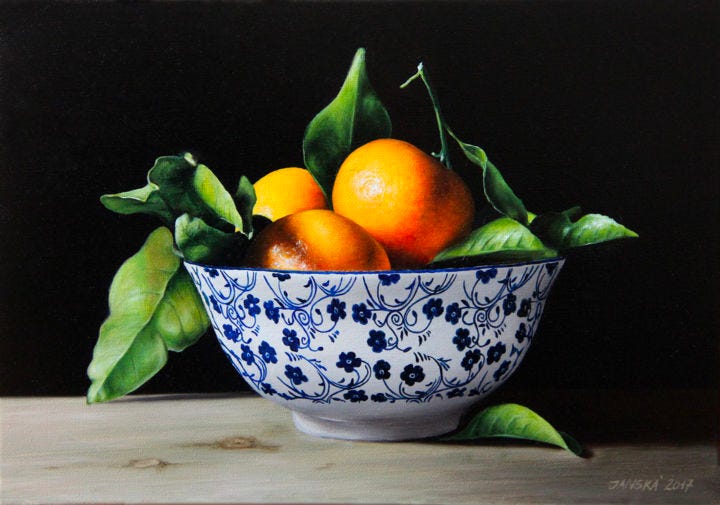

The short stories of the collection she’s building each brood in ekphrasis in their own way—I think of the way that in titling one story “Bowl of Tangerines” she is at once in conversation with a wealth of artists—orange fruit, blue bowl. One degree away.

Cassie and I have both had the pleasure of reading Jeremy Jones’ backdoor memoir-in-progress, which builds from the story of his finding an ancestor’s journals, written in code, on the internet—then reading them, and finding his experience as a father and a son in the here & now embroidered onto those pages. Amina Cain likewise writes about Virginia Woolf’s diaries—and her aunt’s, which she inherited in “a large red duffle bag”—“I am almost afraid to reach them, in the same way I was afraid, when reading my aunt Allison Miner’s diaries, to read the entries close to her death, how sad I knew it would feel, and yet with my aunt it was important, a loving accompaniment.” Cain : Allison Millner :: Jeremy : ancestor, as they all are to Virginia Woolf. Perhaps Amina Cain would be interested in blurbing, reading, reviewing, interviewing Jeremy (not to speak for her, but Jeremy’s future publicist, you should see)—either way, their else’s are in conversation.

Jenny Sadre-Orafai’s Dear Outsiders is near-perfectly described in how Cain describes Amanda Ackerman’s The Book of Feral Flora: “and though I wouldn’t categorize the book exclusively as fiction, it is “near fiction” no doubt, and as a fiction writer I am interested in this nearness. It is also near poetry.” In prose poems, the siblings narrating Dear Outsiders collect like souvenirs of the tourist town where they live, Jenny Sadre-Orafai does the lyric work of constructing place, but churns us, too, through a narrative grief. Near fiction—near poetry. (if you want to read this, AND YOU DO, I PROMISE, email me!!)

And then there’s Sydney Hegele, whose novel, Bird Suit (another tourist town book, this one coming from Invisible Books in 2024!), as well as everything else they’re writing, rings in Cain’s “I want intimacy and sentences both.” The literary embrace of a book with a story, but larger than plot, a sort of vacuuming atmosphere. Referencing John Gardner’s The Art of Fiction, Cain writes, “Again and again in novel after novel, plot gets in the way of detail. It destroys the dream.”

Conversations with my clients help me find them everywhere. What they read when they were writing their book, yes, but also in everything else that we talk about. Andrea and I talk about Patti Smith, we can’t help it—my client Lauren Haddad and I, every time we talk about her novel, talk about Twin Peaks, or more largely, David Lynch. (“What makes Lynch a genius is that it is impossible to tell the flaw from perfection,”says A Horse at Night) In my pitch for Lauren’s book, Twin Peaks is our first comp. It’s the conversation that seemingly moves away from your book, sometimes, that gets us even closer to the core of it.

Whether you’re querying your book or pitching it for reviews, it may help to think of the process less as simmering your work down to gimmick—angles, the way you pitch your book, should never depreciate the pages down only to their hook. What if you were instead starting a conversation about what you’ve written?

If you couldn’t tell, my favorite way to start talking about a book is to describe where I found it. I can’t help but talk about finding M Train, because it was so foundational to the way I really found myself rooted in books (read: I am someone who adores M Train, but I can’t shake a Myrtle Beach shadow).

This is the way we’re pitching Donna Spruijt-Metz’s General Release from the Beginning of the World now, too—When you meet MacDowell fellow Donna Spruijt-Metz, she is clearing out her closets, letting go so that she won't–like her late mother–drown her own daughter in what she’s saved. Or maybe, drown her in the question of what she didn’t. Because Donna’s collection is, itself, a collection of the things of her late mother’s estate, which she is throughout the book clearing out, this feels like the starting point of the conversation, where we find her.

Prompt: Where would you love a reader to find your book? Your local bookstore? Left on a table in the diner that you’ve eaten at every Sunday since you were knee-high? Floating on an abandoned paddle boat in the swampiest park on the coast? Make a list—and then, think about whether you should read there, whether they might carry your book.

When I set out to talk to you about Amina Cain, I talked about literally everything else: Heathers, Kevin Bacon, every book at the forefront of my mind right now.

Prompt: Go talk to someone about what you’re writing, but let the conversation move—do you talk about what inspired the writing process for this book? (I loved hearing Lynn Melnick on Fully Booked, describing how she started I’ve Had to Think Up a Way to Survive with just the question of what would happen if she just wrote about Dolly Parton for a year. I wonder how many other books started with a “what if”?) What does your book remind the other person of? Who do you talk about? List your else’s or else.

Side note! After a month of wishing I would, I finally started writing this post during LongLeaf Review’s December write-in, moderated by Stephanie C. Trott, in the last month of her position as the magazine’s Editor in Chief. While the write-ins are on hiatus, I could not be more thankful for those little gathering spaces.