THE BIG OL' PATTERN MACHINE.

in which I talk about Booktok, and numbers, and publishing, and "tradition," and cycles & patterns, and comfort.

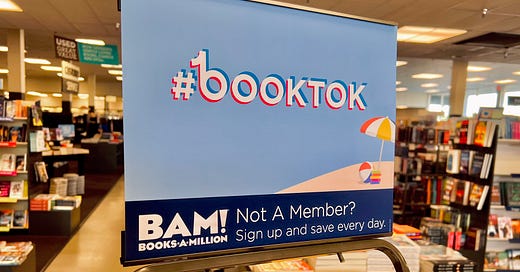

I guess this week I want to talk about something that has rankled me for some time, and recently got a big ol’ shoutout in the New York Times. “The Tiktok Best-Seller Machine.”

Where do I start this newsletter? I think I’ll start with the fact that as we enter red scarf “all too well” season, when quite literally, nothing is well, a lot of us are looking for comfort. My client Daniel Dockery (his book Monster Kids is out October 4th!) has a specific day where he breaks out the pumpkin spice cold brew creamer. Great British Baking Show has returned with a new crumble of homebakers (two episodes in and I’m rooting for Sandro, but I think Syabira can BAKE), and we’re thinking about the movies we’re going to rewatch during the on-again-off-again holiday season. In my family, it’s a Nora Ephron jam like You’ve Got Mail, and in spooky season it’s the dueling witch classics Hocus Pocus and Practical Magic.

Turns out for comfort, patterns are incredible self-soothing. But we knew this right? (all the doomed to repeat quotes). Archetypes exist for a reason. Vonnegut created his eight story shapes. Fifth grade teachers are talking to students about four types of conflict. See the pattern? Typecasting. Archetype. Stereotype. In her book, Body Work, Melissa Febos grapples with archetypes and fighting against the narrative we’ve been told about ourselves (and we believe about ourselves) to find new meanings. Here she is chatting with Sarah Appleton Pine for Ploughshares talking about the comfort of grafting.

Not only is it comforting to rewatch things we’ve loved in the past. There are other reasons why we turn to familiar stories: nostalgia, choice and decision fatigue, familiar escape, emotional expression, the bubble of safety, and psychological payoff. The books that are most successful on Tiktok, are also accessible, familiar narratives. And they are usually successful anyway because of this. I’m not sure why we’re writing about Booktok being this great equalizer in the New York Times. It is, in my opinion, yet another mechanism of big publishing.

Madeline Miller, a scholar of Greek, twists Greek myths—something, I would argue, the American school system has held up over other types of stories. The Song of Achilles is a book about Achilles and Patroclus. It’s beautiful, intimate, heartbreaking, has every element of a good drama (I loved it & it has unexpected plot elements), but at center, it’s a story we know well. Colleen Hoover is arguably writing what Grey’s Anatomy and Friends are to television, but with books. She has a formula (again, not a bad thing) and it works. It’s highly dramatic, romantic, full of tension, and they’re entertaining romps. Same with Emily Henry—one of her books is literally titled Beach Read, a trope in trope packaging (happy! bright! beach!). Sally Rooney also falls into this camp (I don’t need to hear the arguments that she’s more literary), she’s THE drama.

This side of Tiktok is also really white. It’s part of the self-fulfilling publishing prophecy about what sells. It’s why every editor is telling me they’re looking for book club and upmarket reads. It’s not a booktok machine, it’s a trope machine, it’s a convention machine, it’s a tradition machine.

Booktok is broken-up in a similar way to all of publishing. It’s mass audience / commercial (romance / thrillers / mysteries) + “traditional” book club readers and then … the rest. BUT Booktok isn’t just these already-bestsellers becoming even larger, there are niches to Booktok.

There is Literarytok (where Carmen Maria Machado reigns) and other forms of genre-driven booktok, Classics Booktok is HUGE, spicy Booktok, LibraryTok, YA Booktok, Leigh Bardugo has a new book out Booktok, identity-driven booktoks, my personal favorite is Sapphic Booktok, and there’s Nathan who is holding nonfiction booktok up on his shoulders.

That’s not totally true about Nathan—the girlies are all reading Atomic Habits and The Body Keeps Score because if we have one thing, it’s anxiety. These books also do really well on Tiktok: your organization books, your books for bullet journal babes, for 75 Hard Tiktok, your books on manifestation, books for tarot and witches and alternative spiritual lives, books for girls who go on Hot Girl Walks (the new it girl narrative?). What I mean to say is that Booktok is, like a bookstore, a categorical system of finding books. Where your ideals live, what your personal narrative says, who and what you connect with, is where you’ll be finding and buying books.

I have also started to see Booktok infiltrate publishing. In three ways, one that I have an opinion on, and another that I’m in wait-and-see mode, and a third that I’m watching happen in my job.

The first is that agents are looking for folks on Booktok who want to write books. Plain and simple. If you have a big platform, you’re being poached by agents. The number for Instagram that publishers told me a few years ago was 300k followers, but that’s before we were looking closer at engagement, so who knows what the successful booktok-to-book-deal numbers are.

The second thing I’ve seen change since Booktok gained speed is the way we’re describing books in both synopsis and publicity pitch. Publishers are turning toward using more trope language to sell readers on a book. And by trope language I mean, “enemies to lovers.” We’ve seen these in Twitter pitch contests, but we’re starting to see them as part of the book’s sales package, which is interesting. It’s another way to categorize, sure, but it means we’re reading within a mold smaller than genre. We want to know that the story (the plot) will fit an expectation.

I don’t think most of us are thinking about why we read, it’s more of a subconscious brew, but I wonder what it might look like if we really sat down and tried to figure it out. If it might read like a compass through our personal histories, if it might point to who we are, what we believe, the narratives we’re telling ourselves about ourselves and the world. I’m curious how the why we read question answers our own patterns.

How does, for instance, the why at our core and the sales packaging of books we read, match up?

The third way that Booktok is influencing the publicity market is through what big four publishers are calling “blog tours.” Now blog tours have been around for a while and they used to require an actual blog post about a book—as in we’ll send you the book, you read it, and you give your personal opinion in writing. As a book blogger originally (2010 baby!), it was my greatest thrill to get a PR package from publishers. Some Booktokers charge equivalent to other influencers for a post (in the thousands).

(I swing back and forth on the pendulum of whether bookstagram and booktok should be paid. Today, I’m not sure where I land. In an ideal world, of course. But also some people have to do art for art’s sake. Some people will never make money on their writing. Does that mean they shouldn’t write? What does it mean to build an audience as an “influencer” of books / how much does one bookstagram post influence sales—I don’t know. Charging for promotion, beyond the actual book or swag I mean, cuts out independent publishers completely, so that makes me wary. But also, people should be paid! AH!).

Lately, I’ve been seeing blog tours where the actual reading of the book isn’t necessary. It’s not an organic, hand-selling technique, it’s an aesthetic tour. The game is this: HarperCollins paid fifty bookstagrammers or booktokers to take an aesthetically pleasing photo of [insert book] with a caption “blog tour!” (in a series of dates—one a day for a month or two) and that will fit the “Rule of 7.” The game is no longer personal storytelling and personal connection, but aesthetics.

I’m going to be real with you (and maybe I’m old), I don’t like this at all. It’s a money grab that’s only available to big publishers, it removes all conversation between writer and reader, and it returns books to cultural objects rather than a means of cultural conversation. It’s just … gross to me. Any form of social media advertising is going to be about a book’s design and aesthetic—Booktok, at least, is a video, but this blog tour business capitalizes on the fact that we’ve reached an era of social media where we can’t even be bothered to read a caption on a photo. It must be worth it for sales because I’ve seen it in every book marketing packet from the Big Four lately.

You might think that this would push publishers to pay designers more and YET I haven’t seen that conversation anywhere. With Bookstagram and Booktok, the cover appeal of a book becomes just as important as what’s in those pages, which means it is also, you guessed it, important to a marketing eye to “brand authors” starting with their debut. (Branding as in fonts, colors, font size of name, etc). Patterns, patterns, patterns.

Of course this is also a conversation around who big publishing is trying to reach. But if I’m being real with you, no matter the house I’ve sold to, I’ve seen the same marketing plan again and again. (I wish I could share it with you but I don’t want to be sued).

What patterns don’t usually account for is freshness, originality, (in some ways authenticity), divergence. It’s the same conversation around comps. If everything we sell must rely on something that came before it, what does that mean for marginalized writers? For translations? For writers writing about their identity outside of “expected narratives?” For writers outside certain class structures?

I was speaking to a class a few weeks ago, and the very last question a student asked was, “if we’re just reading our own genre for comp titles and to see what’s out there, doesn’t that encouraging mimicking and tamper originality.” And readers, I’m still thinking about it.

If we tell writers, read WIDE, what do we really mean? If we tell writers, they must convince us their book has merit because of what’s sold well before, what do we really mean? I love this tweet from Matt Bell describing a quote from Alexander Chee last week. It makes me wonder WHAT parts of me I’ve been feeding with what I read. And what books truly light me up. Lately, I don’t want to read lyric essays, but that is what I write. A conundrum for sure, a little scary too.

These are questions I’m still figuring out as I look for new books to represent, new books to publicize, and attempt to sell what I believe are fresh narratives to an audience of publishing (big four typically on the agenting side) that really just wants what’s familiar. (I should say if you’re not a debut, you have more wiggle room here). But also, rest assured, the big four is discovering what does well at the independent and smaller press level, and then copying it and calling it fresh. (Your acquiring editors are NOT to blame for this, they are not the ones who determine money!).

Anyway, we live on a big rock rotating in space—it must be damn hard to write something that lives outside the cycles of that. I can’t wait to read it though!

I don’t BookTok. I barely Instagram. I do have readers. Thank heavens for publicists, but nothing makes small press writers feel more inadequate than the latest fad that the big houses throw money at. We try to eke out money to hire our own publicists knowing we can never pay them enough. I understand why some young folks want to grow up to be influencers. Who doesn’t want to be courted?

This one caused me to think about why I feel so let down by the trope machine as a reader in the last several years. One, books that I'm expecting to be at least slightly literary, are more and more often turning out to be really a basket of tropes. This summer at my mom's house I came across a nice-looking hardcover that seemed appealing and was set in a small town in my region. My mom and I thought it would be a fun beach book about women's friendship with local setting appeal. The word literary was on all the jacket copy. And. it. was. just. too. tropey, even for my mom who has good taste but is less picky. It's maybe not even the tropey-ness, it's the absence of anything else. My other complaint is maybe another side of the same complaint, which is that even when I'm looking for a particular commercial genre that I have read a lot, it seems harder than it used to to find *good* ones. Even my kid, who reads kind of between middle grade and YA, is complaining that "these books are all the same." It's to the point where if I'm not buying a book from an independent or university press, I'm probably buying one that was published more than 10 years ago or (especially) first published outside the US. I guess what I'm saying is I like familiarity and commercial books sometimes, but I think big publishing is not doing this well.